Cross-Validation and Brazilian’s Biometric Irises

It’s through a small door in the Avenida Paulista region, in São Paulo, that people arrive one by one, with cell phones in hand. They downloaded an app at home, scheduled a time, and waited their turn to scan their irises in exchange for cryptocurrency. In line, most people can’t say what it’s for. Most are there because of the money.

This is a report made by CNN Brazil in January of 2025. The mysterious organization is asking some Brazilian people to scan their irises in exchange for some financial return. It is for AI data collection. This practice raised some questions about the data privacy of the individual, but behind this news is far more intriguing than simply an ethical discussion. It is necessary to introduce some machine learning practice knowledge to understand the de facto worrisome challenges.

1. Review

In the text:

The explanation begins with the No Free Lunch Theorem: without a better model a priori of their application to the dataset, a metric is necessary to evaluate which model is the best, and the metric that we discussed is MSE, which is stated as follows:

Based on the MSE, we evaluate a model or more and the model’s ability to describe the model. Then, the problem of describing the dataset is classified into two categories: underfitting and overfitting. Underfitting is when the MSE is very high, and overfitting is when the difference between training MSE and test MSE is big. At last, since the overfitting concept is too complex to understand, the example of the allegory of the cave by Plato was used to explain this abstraction. Now, continuing our journey: since there’s a “skill” for each model, is there a way to improve it?

2. Cross Validation and iris issue: grouping the people

Our object is to improve the model to reduce training error but not generate overfitting. Since the model is statistical(or not deterministic), we can use a repetition of sampling the data, repeat the modeling process, and then get the mean of MSE. This is called Cross-Validation. Let us put the definition of cross-validation:

Cross-validation: a procedure that is based on the idea of repeating the training and testing computation on different randomly chosen subsets or splits of the original dataset.

Since underfitting and overfitting are problems of precision prediction, and when we suppose that there is only one model that we can use, the only way to improve the model prediction capability is to let him see more cases(more data). When it is impossible to acquire more data, we can take out a part of the data, train the model with the rest of the data, and repeat this process again. Or let’s say, instead of a simple sum of the dataset, we now reduce the dataset to train the model but repeat the process and then get the mean of the training error.

There are many ways to do this process; we will list some classical ways using an example of the biometric iris data. Biometric iris data is an underestimated biometric data:

Random formation: The intricate patterns of the iris (crypts, furrows, ridges, and freckles) develop randomly during fetal growth and are not genetically determined. This means even identical twins have distinct iris patterns.

Low probability chance of match: The iris contains approximately 240 unique “identifiable features” (e.g., more than fingerprints), leading to an astronomically low probability of two irises matching by chance.

Mathematical evidence: Studies (e.g., Daugman’s iris recognition algorithms) estimate the probability of two irises matching is less than 1 in 1⁰⁷⁸ — effectively unique.

So, considering the biometric iris data nearly as an ID, how will the data collector use Cross-validation based on biometric iris data?

2.1. Leave-One-Out Cross-Validation (LOOCV)

Suppose that there are n people in total. We take out one line of the data(which is a person with a unique identity of biometric iris and the person’s feature), train the model to predict the people’s salaries, then make the devolution of this line into the dataset and take out another line of the data(or, another person’s data), train the model to predict the people’s salaries again, then make the devolution of this line into the dataset, etc. After we do n times of this training process, as there are n individuals, I will try to predict the rest of the n – 1 people’s salaries. Quiet frightening, right?

This process is called Leave-One-Out Cross-Validation(LOOCV). A line of data(person) is retreated, and we train the model with the rest of the lines of data(the rest of the people). We repeat this process until all lines are reached, and in the final step, we calculate the mean of MSEs.

In this case, each iteration of leaving one out is like seeing the impact of one person in his absence on training data. So, analogically, what will happen in this model if the person is left one by one?

2.2 K-fold Cross-Validation

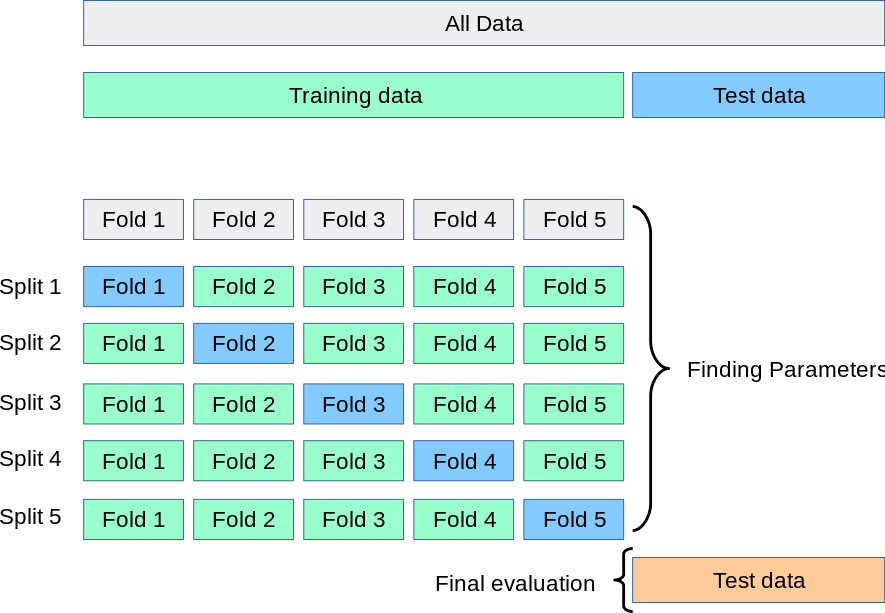

Now, imagine leaving out not one person but a group of people. Dividing the group of people into K quantity of groups, then choose one group and let it leave out of the training dataset, and then train the model with the rest of the K -1 group. This is called K-fold Cross-Validation. This time, in the absence of a group, we see the impact on the training model.

Remember, we divide K groups equally, or we have the same quantity of people in the same group. Please see the figure.

2.3 Stratified K-fold Cross-Validation

We come to the last serious question: let us suppose that the data contains a lot of people from one continent, one country, or one race and lacks data from the others, this means that the data is imbalanced. One strategy is to divide the group in the sense that it represents equally an element. So in the case of the country, we represent an equal quantity of persons per country in the group, this is called stratification.

Stratified K-fold Cross-Validation is a variation of K-fold cross-validation that ensures each fold retains the same class distribution as the original dataset. It is a variation of K-fold where the folds are created in a way that each fold maintains the same proportion of observations for each class as the original dataset.

3. Data Diversity and Brazilian Biometric Iris

As earlier said, when the data is imbalanced, one way to overcome this problem is by stratification. However, this is not the final solution since the general imbalance exists. When we lack data on a specific group, the most correct way is to collect more data about this specific group.

In the case of the biometric iris databank, when we lack data on a specific group of people, we will go to find the specific group of people to diversify the dataset. One way is to go to each continent or country to access their iris data, but how about accessing data of a country that inherently is diverse? This is when Brazilian’s biometric iris data is becoming interesting. According to the data, Brazilian Racial Distribution (2022) Estimates is

Multiethnic 47%

White 43%

Black 9.1%

Asian 0.8%

Indigenous 0.4%

The most important part of this data is that Brazil, as it has a strong presence of multiethnic groups, is particularly interesting to collect their data. People always say the consequence of this data collection is big and disastrous, but without any knowledge of why the consequence is big: Brazil’s multiethnic demographics provide a rich dataset to train algorithms, reducing biases that plague less diverse systems.

So, diversifying this databank is their ultimate goal: to find people here in Brazil and pay a little reward for them. Lack of biological education and lack of financial resources leads to some Brazilian people selling their irises data, which means selling their ID. Watch out; the data collection enterprises are now beginning to collect our IDs.

Leave a comment